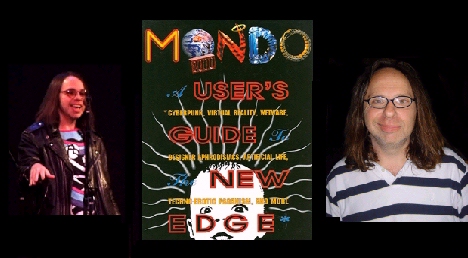

The following is a possible introduction… or possibly one of several introductions or possibly an opening chapter to the Mondo 2000 History Project book. It's my story of particular points in my life that I now see as the run up toward starting High Frontiers magazine which became Reality Hackers and then MONDO 2000. Since I was the sole possessor of the idea to start the initial magazine, I believe there is some justification for this personal narrative being the opening salvo, however I'm not stuck on it and I'm happy to hear all feedback.

Morgan Russell, who is co-editing the book with me, said this text works as an introduction to the book and is "naïve" (in a good sense). I think that's correct. Hopefully, a somewhat more worldly perspective is implicit in my current writing of these memories.

If you like the writing here, please let that be a motivation for continuing to spread the word about this Kickstarter page. We would love to be able to dole out a few dollars beyond the money needed for management of the open source site to pay us and any other super-contributors a little bit for our time; to pay for some transcription of recorded interviews; and to get rights to reuse some already published materials. So keep it coming, please. (And if you don't like the writing here, then you can buy us the time to improve it!)

Besides linking to it, the text below is available to reuse/post elsewhere. I ask only that you give attribution to R.U. Sirius as the author and then link to http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1502076070/mondo-2000-an-open-source-history.

The MONDO 2000 History Project: An (Possible) Introduction

Let the story beginning in the Spring of 1967. I am 14 years old and in 9th grade. It's early evening and the doorbell rings at the suburban house in Binghamton, New York where I live with my mom and dad. It's a group of my friends and they're each carrying a plastic bag and looking mighty pleased. They come in, we shuffle into the guest room (where the record player is kept) and they show off their gatherings — buttons ("Frodo Lives!" "Mary Poppins is a Junkie" "Flower Power"), beads, posters (hallucinatory), incense with a Buddha incense burner, and kazoos. A lonely looking newspaper lays at the bottom of the pile, as though shameful, the only item unremarked.

Without realizing the implications, I happen to throw side one of Between The Buttons on the player. Eventually, the song "Cool Calm and Collected" plays and a kazoo sounds through the speakers. In an instant, newly purchased kazoos are wielded and The Rolling Stones' only-ever kazoo solo is joined by three wailing teenagers, bringing sudden shouts of objection from my famously liberal and tolerant Dad in the living room. It's quickly determined that it's late, Dad's tired, and it's time to send all kazoo-wielding teens packing. As each of the friends moves to retrieve his items, I grab the newspaper to see what it is. There are, I now see, two of them — two editions of something called "The Oracle." It has hallucinatory visuals on the cover and boasts an interview with a member of The Byrds (David Crosby). Vinnie, who had bought it — but who, despite writing poetry — avoids any signifiers of intellectual curiosity as the teen status crushers that they are, feigns disinterest and gives the copies to me.

And that's where it begins, this strange love affair with the periodical, particularly the periodical that has flair and style… where you can almost feel the energy and fun emanating off the pages.

I remember only one thing from the content inside those two Oracles and that's David Crosby denying that he was "some kind of weird freak who fucks ten chicks a day." That stuck in my mind. I didn't know it was possible even to think that, much less print it, much less be in a position to find it necessary to deny being it!

Let the story continue some time in early 1969, I'm 16 and in my junior year at Binghamton Central High School. The student/youth protest movement has fired my imagination — and the more radical the better. The Columbia University takeover with obscenity screaming Mark Rudd! The French Revolution of May '68! The armed black student takeover of the Cornell administration building, just 45 miles away in Ithaca! WoWeeee!

I wanted a piece of it. So I started a high school "underground newspaper" — The Lower Left Corner. Wanting to spring it on the school as a total surprise, I brought in only one co-conspirator (memory fails me, but he was more a collegian liberal type while I hung with the freaks.) Anyway, what we came up with was, I am sure, a completely lame and absurd piece of adolescent indignation. While college students revolted against the war, racism, and authoritarianism in school, we boiled it down to authoritarianism at school. The one thing I remember is that we had a cartoon of a teacher wearing a swastika armband busting a student for smoking in the boys' room. (Eat your hearts out, Brownsville Station!) It was that stupid.

To this day, I consider The Lower Left Corner a great success. Eight pages, Xeroxed front and back and stapled together… we entered the school each armed with a boxful… probably about 80 copies each total, and started handing them out selectively, avoiding the jocks and straights (by the way, straight used to mean "not hip.")

We got to homeroom — official start of the school day. The principle came over the loudspeaker. "Anyone caught with a copy of the paper called The Lower Left Corner will be immediately suspended from school." All eyes on me. Homeroom ends and as the door to the hallway swings open, I step out into my first taste of celebrity. All the jocks that usually threaten to beat me up or cut my hair off are jostling for a copy of the forbidden paper… even thanking me upon receiving. Laughing, I thrust the pieces ‘o' crap into the grasping hands, happy also to get rid of them so that I wouldn't be caught with any copies… and then I waited for the administrative consequences.

None were forthcoming. I had beaten the system… and in two ways. I'd gotten the administration to act out the very authoritarian impulse that we were lamely dithering about in print; and I learned something that served me well through the rest of my career as a high school "sixties radical. " If the authorities think you're political enough to run to the ACLU, they'll leave you alone and bust your intended audience instead!

We created and "printed" one more issue of The Lower Left Corner. As I recall, it was on an antiwar theme and we paid more attention to the quality of the text and design the second time out. This time, we handed them out without any attempted interference. Teachers even used it as a source for classroom discussions. And of course… no one cared.

Let the story continue in Fall of 1971. I'm 19. I meet Tommy Hannifin at a rally against the killings at Attica State. He's shouting the not-so-secret codeword… YIPPIE! We converge and excitedly share our mutual love of the Yippies' funny and fun acid-infused, prankster, wild-in-the-streets take on The Movement as a Youth Culture Revolution. I tell him that I want to create a Binghamton Chapter of the Yippies and start an underground newspaper. And so we did.

I should be clear. I had never thought… even for a moment, about journalism as a craft and/or a career. It didn't even occur to me that I should think about it in those terms. Indeed, to the constant worry of Mom and Dad, I never thought about career at all. I assumed that The Revolution would render those issues moot. I simply reached for the print medium because it seemed like a tool that was accessible. (It was… relatively speaking.) I seem to recall that Tommy, at least, knew something about layout — that you had to get these boards, type out the text, get visuals and paste it all up. And so, we pasted together Lost In Space, Binghamton's little underground newspaper, ripping off a few frames from an underground cartoon titled Nancy Kotex: High School Nurse for the front page. This thievery was utterly naïve. The idea of copyright and intellectual property was unfamiliar to me — like so many things in life that seemed obvious to so many, it hadn't occurred to me. The cartoon just struck us as funny, and when we imagined people getting all upset and offended by it, it became twice as funny. And so I learned about the double scoop of pleasure you get from prankster humor that confounds or freaks people out. You get to laugh at the joke… and then you get to laugh at the over-reaction to the joke.

Like The Lower Left Corner, Lost In Space (changed by issue #2 to Space because movement types told us Lost In Space sent a negative message) was a piece of crap. And unlike the underground papers of the bigger urban centers and hip college towns like Madison Wisconsin and Ann Arbor Michigan, we had no tributes to George Jackson and Ho Chi Minh; we had no quasi-sophisticated neo-Marxian analyses of the movement; no major statements from Robin Morgan about the rise of militant feminism; and probably not much news. Like The Lower Left Corner, Space was locally focused, reflexively against all authority, and juvenile. But it was probably a bit more stylishly written… and it certainly had a puckish sense of humor.

Let the story continue in 1980. I'm 27 years old and a Junior at the State University College at Brockport, New York, near Rochester. (The Revolution having left me stranded.) My friend Brian Cotnoir wants to start an avant-garde art newspaper. He calls it Black Veins — which comes from an interpretation of a line from Lautreamont's epic proto-surrealist misanthropic horror poem Maldoror (Les Chantes de Maldoror) — and he signs me on as co-editor. The paper features dark, perversely angled bits of poetry and fiction, but I bring something else in. Since the mid-1970s, I have been nursing a growing obsession with the neuro-futurisms of Dr. Timothy Leary and Illuminatus author/philosopher Robert Anton Wilson.

For the first issue, I have a written exchange with Wilson, performed by the soon to be archaic means of letters sent by mail. (As best I recall) the exchange essentially involves me wringing my hands that the world is a terrible place and that his optimistic weltanschauung may actually be a dangerous diversion. (I would later get letters like that myself at MONDO 2000 and, generally, respond with dismissive quips intended to communicate my lack of commitment to an optimistic — or any — point of view.) My letter includes a pretentious, portentous quote from a Village Voice review of Hans-Hurgen Syderberg's 6 hour film, Our Hitler.

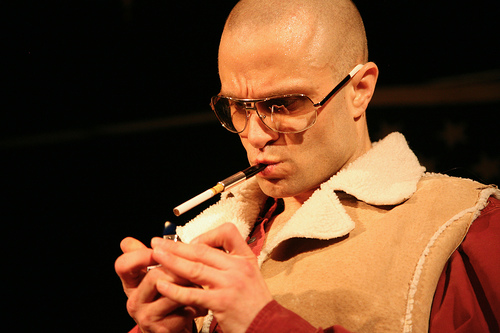

And then word comes that Dr. Leary himself is coming to Rochester on his "stand up philosophy" tour. Brian, his girlfriend Ellen, myself, and our ex-girlfriend Liz pile in Ellen's car for the 30-minute drive to Rochester for the Sunday afternoon performance. Our goal is to interview the Dr. after the show for the second issue of Black Veins and then to film him. I plan to try and incorporate him into an 8mm movie called Armed Camp I'm making for a film class. (Incidentally, that's camp in the Susan Sontag sense.) The film involves, among other things, some 20-somethings playing poker in pajamas using the Aleister Crowley Thoth Tarot deck and then dancing to The Archies "Sugar Sugar" 45 rpm played at 33 (makes the vocals sound sort of like Jim Morrison). There is a vague narrative structure to this odd little attempt and I have reworked it so that it required Timothy Leary to say a few lines.

My posse — myself excluded — is negative about mind-altering drugs and cynical about Leary, and this makes me anxious. As we take our seats, the end of the Pink Floyd album The Wall blasts out of the loudspeakers and the cover of Leary's book The Intelligence Agents — which shows multiple copies of the same baby attempting to climb over a brick wall which appears to have no end — is projected onto a screen on stage. Then comes Side 2 (The "1984" side) of David Bowie's Diamond Dogs. Given his recent byzantine adventures with prison, exile, revolution, and compromise with the powers of state, it seems as if Leary is trying to tell us something. To the final echoes of Bowie singing "We want you, big brother," Dr. Leary walks on stage. Liz mutters a bit too loudly, "Ohmygod, it's Johnny Carson!"

The performance is not particularly impressive or funny, but Leary agrees to be interviewed. He unleashes that famous laser beam smile on each of us, one at a time, and the vibe immediately changes. Instant intimacy. Timothy Leary is now our special pal and we're his co-conspirators. We move into the restaurant attached to the club, order drinks and peruse the menu. Liz, a slightly moralistic vegetarian, asks Leary if he eats meat. "I'll eat anything!" he says directly to her, smiling. It's something that has been said a million times before by both jackasses and geniuses, but it comes out like a blast of freedom. Everybody feels this.

We all have a roaring great time interviewing Leary about life, drugs; his hatred of followers, his futurist theories, and the 1980 Democratic primaries ("If I'd done a better job, you wouldn't have all these pasty-faced white guys running around New Hampshire.") We're all dazzled, feeling like the host of Planet Earth's party had lifted the velvet rope and let us in. As we finish the conversation, Ellen urges me to ask Tim about appearing in Armed Camp. I'm feeling shy, but I share the script — such as it is — with him and point him at his two-sentence part. "What's it about?" he asks. A bit flustered, I blurt out, "Nothing really." He laughs and looks at my friends. "Thaaat's wonderfullll, isn't it? Nothing. Isn't thaaat wonderful?" Everybody laughs, including me. He won't read the lines but he will let me ask him a question and film his response… which turns out to be useless for my movie, but a treasure (that I will soon lose) nonetheless.

As we wrap up, Tim asks for a ride back to his hotel. He shrewdly picks Brian to dismantle and pack up the photo projector he'd uses to backdrop his talk. As we head to the car, night has fallen. Liz is pawing Dr. Leary, while they both gaze up at the stars. He points and describes a constellation or two. In the car, Liz continues to stroke and flirt, offering to come up to his hotel. Leary tells her she is very beautiful and wonderful, but he's married. As "Sympathy For the Devil" pops up on the mainstream rock radio station, we pull up to a raggedy-ass little hotel that's near the Rochester Airport and the good Dr. takes his leave of us.

Let the story continue in early November 1983. I am 31 years old and have just recently moved into a weirdly straight (see above) shared household in Mill Valley, California, a 'burb of San Francisco. The house is made up mostly of sedate 50-something recent converts to new age philosophies — an oddly pale white man who emanates a bland but likeable passivity seems to be the eminence grise of the household scene. And then there's a Hindu Hippie couple around my age that lives in the back room. They smoke pot (I can smell it) and they pretty much keep to themselves.

I have moved from Brockport, New York to the San Francisco Bay Area (starting off in Berkeley) with a "note to self" in my pocket — the only thing I could write during several months of writer's block, after a briefly successful academic and small town rock and roll career as a writer of fiction… and writer and singer of song lyrics. The note contains my California to-do list: "Start the Neopsychedelic Wave. Start a Neopsychedelic band. Start a Neopsychedelic magazine."

In late 1980, having written two darkly comic short stories to great local academic approval, and even winning a scholastic award (best fiction) for one of them (titled "Glib Little Holocausts"); having written darkly comic lyrics for a punk-tinged rock band (called "Party Dogs") and performed to some approval in both Brockport and Rochester; and looking ahead vaguely to either trying to make a run at a career as a rock and roll eccentric or hiding in obscurity as a writing professor; I came in for an odd reckoning — an interruption, really. It was a really good LSD trip.

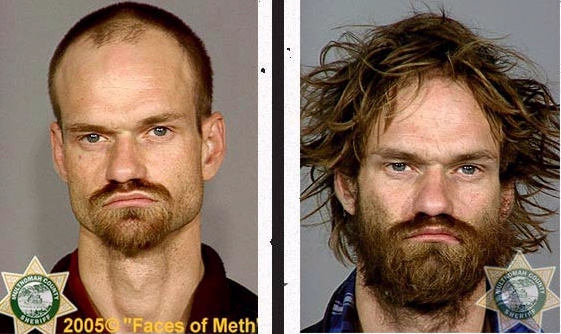

Two days after the murder of John Lennon, laying in a room in a small apartment in which the heat pipes played oddly angelic music that had gone heretofore unnoticed, my girlfriend Lisa and I laid face to face, took the clean 250 microgram doses of liquid LSD-25 we had gotten from the colleges' hippyest Deadhead and made off for the cosmos.

Up until then, even my best trips had been fraught with ambiguity. My friends and lovers were weird. My hometown was relatively small… and contained parents who worried, and hostile lawmen and jocks who knew who I was. There was always at least the hint of trouble or shame — the feeling that my neurological nakedness was something to hide and someone lurked around the bend ready to give me a bad — or, at least, a strange time.

Now, there I was, safe and high and with a girlfriend who I actually liked and felt comfortable with, primed by my readings of Leary and Wilson to tap into an elegant symmetry, a generosity, even a sense of frivolity in the heart of all-that-is.

At first, the acid hit strong. It jolted up and down my spine like kundalini lightening, then shooting out the top of my head in a glorious explosive overabundance — an excess of multicolor wow! and then it smoothed over into an endless and sumptuous multidimensional layer cake of pastels filled to the brim with warm congratulations at having arrived. Later, it took me into deep space, and the heat pipes, which had been playing a pleasant kind of Tuvan throat music drone started, instead, to play John Lennon's hit song, "Starting Over" and, well… the message seemed clear. What the Lizard King had said was true: "Everything must be this way."

The aftermath of the trip found me disastrously happy, playful, optimistic, frivolous and energized… and writing about the coming of a Neopsychedelic Wave in lyrics and fiction. In the real (small) world of Brockport, New York, I'd shifted into a master's course in Fiction Writing, and attempts to give expression to my new head in that context weren't working. What came out was the sort of gibberish that has been produced before and aft by so many in the throes of psychedelic wonder — shards of flashy words that tried to convey – no, make that impart the energy of being aliver than thou to the recipient with FLASHY CAPITALIZED WORDS. Finally, after a couple of floundering semesters, I heard the siren call: "California is the place you oughta be!" There was really, after all, only one state from which to start a Neopsychedelic Wave.

So I'm sitting in the living room here in Mill Valley in 1983 just sort of gazing out the window when something bordering on an apparition appears. The Hindu Hippies plus their friend, a tall thin man in white robes — a visitor who occasionally slinks in and out of their room to use the bathroom — are opening a side door, and walking with them into the very back yard that I am gazing upon is a tall, thin, curly haired man, speaking something not quite audible in a familiar, nasally voice.

I recognize the man. I had attended a lecture he gave at a place in Berkeley a few months earlier. It was something about magic mushrooms and UFOs. In a nasally voice that reminded me of Jello Biafra, the man — Terence McKenna — had woven an astounding linguistic spell, rich with references ranging from Learyesque projections of future space architectures and superhuman amplifications to McLuhanistic media meanderings and, to top it all off, erudite descriptions (damn, why couldn't I do that?) of psychedelic experiences… including one that involved something along the lines of forty days and forty nights on mushrooms in the Amazonian Rain Forest during which he "channeled" a message from the logos that was calling us forward through time and using the acceleration of technology and consciousness and social crisis to bring us to some kind of psychedelic singularity in which exteriority and interiority would trade places!

Well… far out! But what the fuck is he doing at my house with the Hindu Hippies!? Here am I, on cosmic assignment from something or other to start the Neopsychedelic Movement and feeling meek and quiet and ill prepared and there's this McKenna guy at my house. They quickly retreat into the back room. It takes me a good half hour to work up my nerve and tap on the door.

What happens next is (like an alien probe) wiped from my memory. Let it be said — and many will attest to this — that Mr. McKenna always brought the powerful fucking weed with him when he came. All I know is that, somehow, at the end of the visit, which probably lasted all of an hour, Mr. McKenna is handing me a baggie with 6 grams of dried psilocybin mushrooms and a joint of his way-too-strong pot and telling me (McKenna familiars… hear the nasel): "Eat these on an empty stomach. An hour later, go into a darkened room and smoke this joint. That will get you where you want to go."

So it's about a week later, and it's Monday, the start of a Thanksgiving weeklong break in my job selling season ticket subscriptions by phone for various Bay Area arts organizations. I have decided that tonight's the night. I will take the 6 grams of mushrooms late that night and lie in the dark in silence in my room and I will make contact with The Others — the alien intelligences that Mr. McKenna says are available on the Psilocybin frequency (when you take enough) — or I won't… and either way, it will be a groovy trip.

I have decided to try a borderline fast — nothing but toast and water (and my morning cup of coffee) all day. It's a big mistake. It's around 5 pm and I'm heading home after strolling into town and I start to pass the McDonalds on the corner when the hunger overwhelms me and the biological robot commandeers my brain. By the time my brain returns to ordinary consciousness, I have downed a bag of Chicken McNuggets and a small bag of fries. Now I'm unhappy with myself and I'm deciding that I've blown the opportunity. No trip tonight.

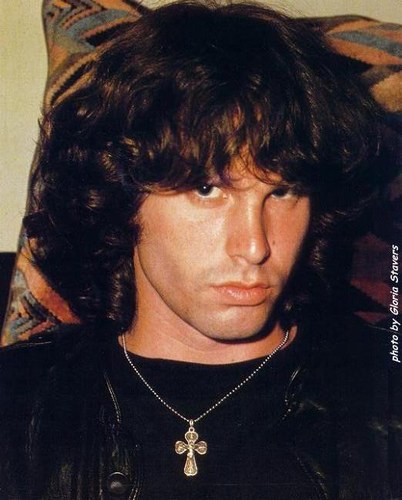

I get back to the house and, oddly, it's empty. It's a large household, yet no one is home. A thought grips me. If they all stay away for an hour, I have a chance to get off on the mushrooms alone, having the run of the house during those energetic, intensely physical early moments that occur when you first come on to psychedelics. Then, I can hide out in my room with the lights out for the remainder of the trip. The time is nigh. I chew down the biggest batch of ‘shrooms in my life by far and I find myself pacing the house, nervously. Suddenly, after about 20 minutes, it slices through me like a shard of angry glass. A shattering angry splintery energy thing is outside me lacerating me and I am in everything's sights and all-that-is is pissed at me. The house cats start scurrying around yowling, running furiously, scratching at and trying to climb the walls. The suburban Mill Valley street suddenly looms very small and enclosed and conservative, and me… Mistra Inappropriate… not in control of my basic social signals and I'm now being lacerated by demons from a peculiar occult/Rolling Stones mirrorworld for abandoning them back in Binghamton, New York. Multiple car engine noises scrape the insides of my gut (In reality, it's around 6 pm, the time when people in the suburbs get home from working in San Francisco) — each one of them very likely carrying narcotics cops or agents of some hostile control system and, worst of all, I see it like it is now… They're the good guys and I am cast out, having done wrong; having eaten magic mushrooms on a corporate McDonald's stomach… heedlessly. I stare out the front window expecting incoming — hoping merely that the inevitable death is not too tortuous. And then it happens. A car actually stops right in front of the house. This is it. It's over! But wait. The doors open and several clearly preoccupied corporeal and painfully ordinary humans emerge — all my housemates. They are opening doors and the trunk and picking up grocery bags. In an instant, things shift. The immediate danger lessens but does not disappear. I still may be attacked by angry beings, but right now I have another challenge. I have to act normal. I shuffle to the front door and open it, thinking that the best strategy is to wander out and offer to carry grocery bags. I take one step outside. Can't handle it. I go back inside and close the screen door. Now I've given myself away. But the roomies walk in the house, preoccupied with their normal activities and blandly saying hello, to which I manage a normal sounding reply. All, that is, except for the Hindu Hippie guy. He makes a beeline for me and looks me right in the eyes. Quietly, he says, "Oh boy. Come with me" and, with his girlfriend, leads me by the hand into their back room. I start to tell him what I've done but he already knows. "You've taken Terence's mushrooms." The thin man in the white robes is lying on his side on a cot looking calm. He has been sitting in there all along. They say very little at first. They bring me a cup of warm tea; have me lie down on a cot, and the Hindu Hippie girl gives me a shoulder rub. I mutter something about demons from a Rolling Stones mirrorworld and start to explain about the friendship I had with a strange and charismatic guitar player who was fanatically and uncannily tapped into Keith Richards almost to the point where the evidence suggested a mystical connection and how we spent five months together in borderline isolation learning the entire Rolling Stones catalogue, and how he played it better than anybody alive except maybe Keith (better than Ronnie, by far), and how we talked long into the night about the occult dimensions of The Rolling Stones and the gut level pagan authenticity of the sex and drugs and rock and roll left hand path to enlightenment and how this friendship had all the elements of an intense sexual affair but without the sex and he started talking about Rimbaud & Verlaine and how it made me self-conscious and I couldn't handle it and then I gave him my song lyrics to start writing originals and he said he lost them and laughed at me and I left town and never spoke to him again.

And this makes perfect sense to my Hindu Hippie friends. I mean, christ… they were California hippies. They were probably at Altamont as teenagers! Demons sent from a Rolling Stones mirrorworld made perfect sense. And then, as I settled into a state of calm, the thin man in the white robes told me his story. Vijaya was a former leader of the American Hare Krishna cult. He had left the group because they had started to behave — as do pretty much all cults — like gangsters, with all the corruption and violence that implies. He still believed in Hare Krishna's brand of Hinduism, but he was part of a renegade group of psychedelic Hare Krishnas. And the Hare Krishna cultists had tried to kill him… and he was hiding out. So here we were, me hiding out from mirrorworld Stones demons and him hiding out, ostensibly, from Hare Krishna assassins, both of us in the back room of a very bland Mill Valley shared household.

While the LSD trip that had sent me to California was a "good trip" and the trip on McKenna's shrooms was a "bad trip," they both propelled me on. A couple of days after the psilocybin trip, the resolve to go forward with the creation of a psychedelic magazine took hold of me. I contacted Will Nofke, a new age radio host who had done a series of interviews about psychedelics with Albert Hofmann, Timothy Leary, Terence McKenna and Andrew Weil on Berkeley's Pacifica station KPFA, and asked him for the tapes to transcribe and publish the content. He sent me the tapes and granted me the permission. On New Years Eve — as 1983 was becoming 1984 — I stayed home alone. I finished transcribing the last of the tapes — the Leary interview — while watching the avant-garde video artist Nam June Paik host a very special New Years Eve 1984 show titled Good Morning, Mr. Orwell on PBS' Alive From Off Center, featuring many of my culture heroes: Laurie Anderson, John Cage, Allen Ginsberg, and Paik himself. Later I would have my first date with my wife Eve at a Nam June Paik exhibit in San Jose, California and I would co-create a TV show proposal and sample titled "The R.U. Sirius Show" for the consideration of PBS with John Sanborn, the Producer of Alive From Off Center. When the show ended, I channel surfed and found Timothy Leary on a silly, long forgotten entertainment talk show (I have mercifully forgotten the host). It was lame, but still, it was Timmy on network TV. A great signifier for the beginning of a new life. As 1984 dawned, I started reaching out to find compatriots to be part of a magazine that would be called High Frontiers and later Reality Hackers and then finally MONDO 2000.

See Also:

Counterculture and the Tech Revolution

Steve Wozniak v. Stephen Colbert - and Other Pranks

Robert Anton Wilson 1932-2007

Neil Gaiman Has Lost His Clothes

Is The Net Good For Writers?

In 1969-1970, Iggy Pop and his seminal proto-punk band the Stooges lived together outside Detroit in a house they nicknamed "Fun House." (They also

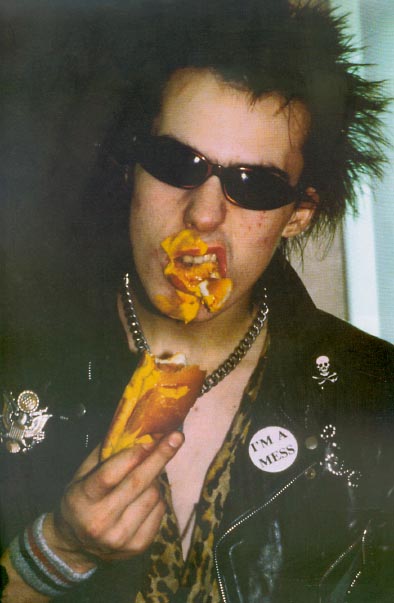

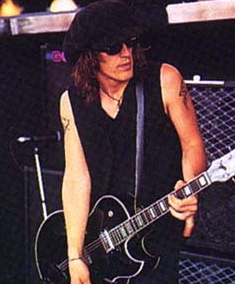

In 1969-1970, Iggy Pop and his seminal proto-punk band the Stooges lived together outside Detroit in a house they nicknamed "Fun House." (They also  Dee Dee Ramone found himself at a party in London, hanging out for a few moments in the bathroom snorting great quantities of speed. It wasn't the sort of place you'd want to hang out for too long, as Dee Dee quickly noticed that the bathroom was disgusting — sinks, toilets, everything was full of vomit, piss, and shit. Sid Vicious — a key figure in the London punk scene but not yet a member of the Sex Pistols — wandered in and asked Dee Dee if he had anything to get high on, so Dee Dee generously gave Sid some of his crank. Vicious pulled out a syringe, stuck it into a toilet filled with puke and piss, and then loaded it with speed and shot himself up.

Dee Dee Ramone found himself at a party in London, hanging out for a few moments in the bathroom snorting great quantities of speed. It wasn't the sort of place you'd want to hang out for too long, as Dee Dee quickly noticed that the bathroom was disgusting — sinks, toilets, everything was full of vomit, piss, and shit. Sid Vicious — a key figure in the London punk scene but not yet a member of the Sex Pistols — wandered in and asked Dee Dee if he had anything to get high on, so Dee Dee generously gave Sid some of his crank. Vicious pulled out a syringe, stuck it into a toilet filled with puke and piss, and then loaded it with speed and shot himself up.

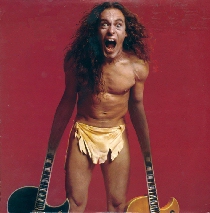

The right-wing rocker Ted Nugent is known for being very antidrug and very prowar. The Motor City Madman happily calls out any pussy-ass traitor not ready to grab a gun or a bomb or a nuke and show those towelheads that we mean business. But back during the glory years of the Vietnam war, this most macho chickenhawk in the Republican firmament went to extremes to make sure his own pussy ass didn't end up in Vietnam, and he used drugs to do it.

The right-wing rocker Ted Nugent is known for being very antidrug and very prowar. The Motor City Madman happily calls out any pussy-ass traitor not ready to grab a gun or a bomb or a nuke and show those towelheads that we mean business. But back during the glory years of the Vietnam war, this most macho chickenhawk in the Republican firmament went to extremes to make sure his own pussy ass didn't end up in Vietnam, and he used drugs to do it.

Japan has a reputation for searching rock stars for drugs. Most famously, Paul McCartney spent some time in jail after going through Japanese customers (see also the chapters: "The Beatles on Drugs" and "Big Busts and Big Deals"). So when Guns n' Roses guitarist Izzy Stradlin was warned by his manager to get rid of any drugs he might have before going through customers in Japan, Stradlin put them someplace he knew he wouldn't lose them — in his stomach. He must have had quite a stash, because he wound up in a coma for 96 hours.

Japan has a reputation for searching rock stars for drugs. Most famously, Paul McCartney spent some time in jail after going through Japanese customers (see also the chapters: "The Beatles on Drugs" and "Big Busts and Big Deals"). So when Guns n' Roses guitarist Izzy Stradlin was warned by his manager to get rid of any drugs he might have before going through customers in Japan, Stradlin put them someplace he knew he wouldn't lose them — in his stomach. He must have had quite a stash, because he wound up in a coma for 96 hours.

In

In  In his mid-1970s heyday, Los Angeles declared "Elton John Week." To celebrate, the glam rock pasha invited his relatives out to L.A. to celebrate. Allegedly, Elton took 60 Valiums, jumped into a hotel pool, and shouted, "I'm going to die." His grandmother was heard to comment: "I suppose we're going to have to go home now."

In his mid-1970s heyday, Los Angeles declared "Elton John Week." To celebrate, the glam rock pasha invited his relatives out to L.A. to celebrate. Allegedly, Elton took 60 Valiums, jumped into a hotel pool, and shouted, "I'm going to die." His grandmother was heard to comment: "I suppose we're going to have to go home now."

In a 1999 High Times interview, Ozzy talked about the time he had the best coke he'd ever had. He said, "I'm lying by the pool one day and I met this guy and I ask him, 'You want to do some coke?' He goes, 'no no no.' I'm whacking this stuff up my nose, it's a brilliant sunny day, and this guy's sitting there with one of those reflectors under his chin getting a suntan. I say, 'What do you do.' He says, 'I work for the government.' 'Uh... what do you do with the government?' 'I work for the drug squad.' I sez, 'You're fucking joking.' He shows me his badge. I fuckin' flipped...flames were coming out of my fingers, man. He says, 'Oh you're all right. I'm the guy that got you the coke.'"

In a 1999 High Times interview, Ozzy talked about the time he had the best coke he'd ever had. He said, "I'm lying by the pool one day and I met this guy and I ask him, 'You want to do some coke?' He goes, 'no no no.' I'm whacking this stuff up my nose, it's a brilliant sunny day, and this guy's sitting there with one of those reflectors under his chin getting a suntan. I say, 'What do you do.' He says, 'I work for the government.' 'Uh... what do you do with the government?' 'I work for the drug squad.' I sez, 'You're fucking joking.' He shows me his badge. I fuckin' flipped...flames were coming out of my fingers, man. He says, 'Oh you're all right. I'm the guy that got you the coke.'"