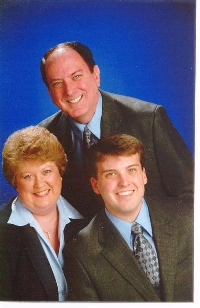

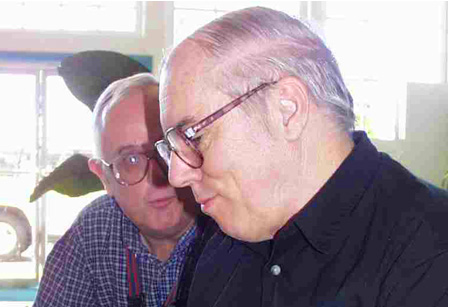

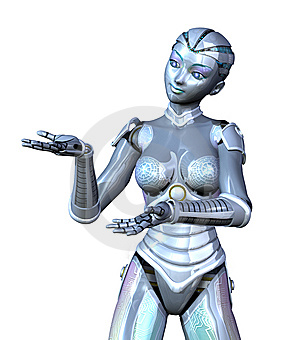

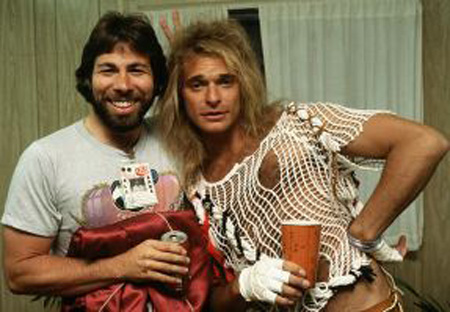

The gonzo author (inset) meets the cover of

his newly-published novel The Panama Laugh

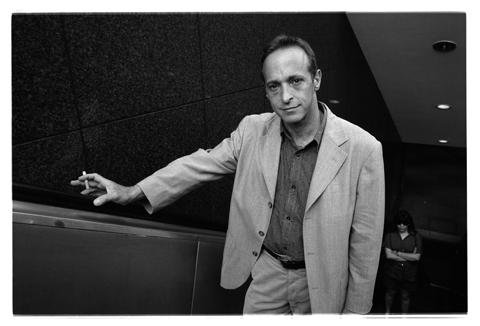

Zombies! Brains! Zombies! It's the first novel ever published by author Thomas S. Roche.

The Panama Laugh opens with a punch — literally — before launching into an unrelenting onslaught of dangerous crimelords, soldiers of fortune, radical fringe groups, and yes, zombies!!! There's a global throwdown with moments of weapons porn — like hijacked nuclear-powered warships and deadly remote surveillance drones — while radical fringe survivors may be holed up in "the Armory" in San Francisco (a real-life building owned by Kink.com).

It's Roche's very first novel — or at least, the first novel published under his own name. (There's also hundreds of horror, crime, fantasy, and, yes, erotic short stories and books that he's written under pseudonyms). Maybe the real question is what makes a man write an "after the apocalypse" zombie novel — after hundreds of hours of writing porn? Combined with a lifelong obsession with vintage pulp fiction, the end result is an original, daring and thoroughly-researched "debut apocalypse," a 300-page buzzsaw that one Barnes and Noble reviewer called simply "exceptional."

I remembered Thomas from his legendary stint as the gonzo technology editor at a web magazine called GettingIt.com, where we'd worked together back in 1999. I decided to track him down for the inside dirt on his mysterious new kick — and to see just how much fun you can have with the word zombie!

10 ZEN MONKEYS: Is there something millenarian in the zeitgeist now — some universal sense of doom, or a desire to laugh and secede from humanity? I'm sorry — every question I'd ask you suddenly seems tainted with a dark obscenity whenever I add the word zombie. "Where do you get your inspiration for your novels...about zombies? Will you be writing a sequel...about zombies? How do you celebrate finishing your first novel...about zombies?"

THOMAS S. ROCHE: Isn't everything about zombies?

I just go ape-shit over good zombie apocalypses. I love them; they're one of my favorite genres. I read a lot and watch a lot and just completely groove on all the incredible creativity involved in zombie walks, all the viral zombie websites and social-networking stuff, all the in-jokes for zombie fans...I just love it. It's a template that takes on so many wonderful forms!

I feel like some of the zombie novels published in the last five years were jumping on a bandwagon. But I'm not going to badmouth them because that's essentially what I was doing, even though it's a bandwagon I've more or less been on for 20 years ever since I read the first Book of the Dead, which is one of the two best zombie books ever published (the other being Max Brooks' World War Z). I think Night of the Living Dead is one of the greatest and one of the most important films ever released. I love Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead and Land of the Dead. And I go nuts over the Resident Evil movies even in the slow parts. I adore Fido. I want to grow up to be Frankenhooker.

10Z: So will you be writing a sequel to your novel about zombies? Maybe "The Panama Laugh Zombies Strike Back"?

TSR: That is actually a question for the publisher. I already know what happens next — but I'm not talking unless somebody pays me!

10Z: Spoken like a true pulp fiction fan...

TSR: I'm hoping there will be a sequel, because the story's really not finished. There are about a thousand threads that lead into other parts of my science fiction mythology — some of them red herrings. Everything I write in the science fiction, fantasy, or horror genre relates to everything else I write in those genres, so the characters, institutions and situations show up elsewhere. I already know what happens — but the cats need kibble, so I'm not talking unless the money's on the nightstand!

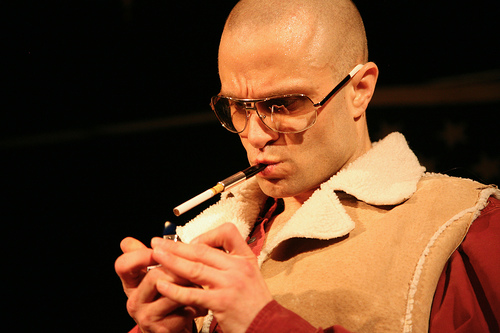

Did I mention writing a mercenary character came kinda natural to me?

10Z: I can already see the influence of all those vintage crime novels. So how did you celebrate finishing your first novel...about zombies?

TSR: I don't think I celebrate, ever. Sorry. When I turned it in, I probably went home and tried to figure out how to pay my rent. I probably read CNN and wept bitterly about the direction our country is going. Maybe if it was a good day, I let myself read an early '60s crime novel instead of trying to work on the next project that might pay me $25 or $50 in an attempt to afford some food...

10Z: And then months later, you're a star! A zombie star, with your name on thousands on horror book covers — along with gorgeous artwork visualizing the doomsday you'd only imagined. How'd it feel to finally see your novel getting a full-color, fantasy-style illustration?

TSR: I just can't even begin to describe how thrilled I was to see such a spot-on representation of what I wanted my book to feel like — at least, the post-apocalyptic segments. Some of the earlier segments might have been a bit more Dick Tracy. But as for the scenes in San Francisco, cover artist Lucas Graziano nailed it, beautifully — and it even has the leopard-print zeppelin! I've never been so thrilled.

10Z: But you always write about such wild subjects. It's hard to believe you've never gotten the Heavy Metal treatment before.

TSR: I believe there have been only two other times original art has been commissioned from my work. One of them was the short story "Anthony," about a doomed punk sex-addicted dildo who gets hooked on mainlining oil-based lubricants. It was turned into a comic book by my friend Anna Costa, in 1992, for a magazine called Puppytoss. (No puppies were actually tossed, don't worry — we weren't that punk). The second time was the story "Headturner," which I co-wrote with Kevin Andrew Murphy, which was illustrated for an issue of Glen Danzig's Verotika comic book. That was more than a decade ago!

10Z: It's still hard to believe, since you've written a bunch of great zombie stories already. (And is it true that some of them are about sex?)

TSR: My pre-Panama Laugh zombie mythology isn't about sex, but it's about sexuality...homophobia specifically. The zombie short stories I have written have just been re-released individually for Kindle, and you can see there's even a zombie bibliography on my website that links to them.

My two other zombie mythologies don't overlap with each other or with The Panama Laugh. In one, which I call the "San Esteban Stories," zombies represent denied erotic urges — violence owing to sexual repression, particularly internalized homophobia. In the San Esteban stories, zombification does not appear to be transmissible. (See The Sound of Weeping and Veggie Mountain.)

There's also another lengthy screenplay on that theme that may become a novel, that's never been published because I only finish novels when people come over to my house and kick me.

10Z: So what happened when you sat down for your full-length zombie-fighting novel? What kind of zombification did you pull out for The Panama Laugh?

TSR: It has a similar thematic intention, but it's not about sex. Two other stories, the podcast "St. John of the Throwdown" and the novella Deepwater Miracle exist in that universe. My story Viva Las Vegas is a totally different mythology, because it was originally written as a submission for Skipp & Spector's Book of the Dead 4, so it's concretely Romeroesque, meaning George Romero, more than the others. Its main character is very similar in voice to the Dante Bogart character in The Panama Laugh.

10Z: I'm remembering that you do a lot of work for charity — and some of it's pretty sexy! Literally — like, you've taught at San Francisco Sex Information since the 1990s, and four years ago, you were even involved in the San Francisco iteration of an event called Dr. Sketchy's Anti-Art School, where even amateur non-artists get to draw sketches of naked models. So what ties all this together? What's the motivation?

TSR: I think it's an impulse toward the Bohemian. I'm easily bored!

I've given informational lectures on such diverse topic as anal sex, oral sex, sex, gender and orientation, transgender surgery and other transgender procedures, intersex issues and disorders of sex development, BDSM and D/s theory and etiquette, necrophilia, bestiality, fisting, group sex, fetishism and fetish dressing, infantilism and age play, recovery from sexual abuse, and about a dozen other topics, as well as facilitating small groups and workshops. At SFSI, the goal is to have our trainees prepared to discuss any sexual topic in informational terms, so we cover a broad range.

10Z: I'll say! I just remember a very "sex positive" vibe at one of the Dr. Sketchy events I attended. You've got ladies taking off their clothes for a roomful of gawking geek voyeurs, week after week....

TSR: Doing Dr. Sketchy's was wonderful. Models would come and get naked but be wearing clown makeup, balloon animal hats, Victorian lingerie — Burning Man type costumes. It was really a blast!

But I'm not by nature an event manager. So by mutual agreement with the event's New York founder, Molly Crabapple, my co-organizer and I passed the event on to the very capable Bombshell Betty. It's a great event, and it was really fun to do.

10Z: In real life you're soft-spoken and compassionate, and yet you've seen more than most men will ever see in a lifetime. After synthesizing it all into hundreds of published stories — including a new violent zombie-fighting novel — what do you think you've learned...about sex, and about violence?

I mean, there's one line in the book that struck me. The gun-toting scumbag says "Without women, we're monsters — and we know it, but they don't. We live our lives in fear that they'll find out." I have this theory that it's all related — that people are now despairing about everything — government, culture, gender roles — and they secretly long for a zombie crisis where it all crumbles and gets replaced by something new.

TSR: I learned a lot, and continue to learn a lot, from the world of trans activism and gender theory. I also think that the "bubble" of a very narrow set of queer-friendly, trans-friendly neighborhoods in San Francisco can serve as an excellent place to stand there and evaluate the gender context of violence, as it relates to the idea of what makes gender in the first place.

In the context of the international arena where brutal violence is the order of the day in many post-colonial and neo-colonial nations, I think it's important to consider issues of what tends to bring perceptions of masculinity in line with violent activity. And to do that in a context of knowing that male and female behaviors are often mutable... As an aside, I believe that the fact that men and women tend to — tend to, mind you, again — have different ideas about that is one of the reasons it's so important to have women in the military in leadership roles, because gender cues get all mixed up when you're talking about premeditated violence, let alone the kind of confusion that happens in combat.

To me, it's critical to have combat decisions made by a pluralistic group with a shared value system that isn't built strictly on machismo. The same is doubly true of law enforcement. In fact, that connection between masculinity and monstrous behavior is probably my primary interest in terms of fiction. My chief fascination has always been with postwar America, and the scars carried by men in my father's generation and a bit older, who fought in World War II and Korea. War requires one to do terrible things, and if any amount of belief in one's principles allows one to forget that, I believe we're in trouble. I'm not going to claim Osama bin Laden or Ghaddafi shouldn't have been killed, but anyone high-fiving about it earns my unremitting revulsion.

I would like to see the United States be a little less pleased with itself, and that's some of what The Panama Laugh is about. "The Laugh" is a symbol for everything we're forced to stuff down in order to turn a blind eye to tragedy. When it comes bursting out...ba-da-bing!

10Z: It seems like some of this novel must've come from all the weird world news you'd covered for — is it over a year? — at TechYum. (Besides flying cars and Bigfoot sightings, there's also weaponry, international wars, Fukushima radiation, and "the face of a Norwegian Killer" — including his Twitter feed....)

TSR: Yeah, there's definitely a strong undercurrent of paranormal obsession, and a real obsession with information technology.

10Z: What about WikiLeaks? You also mention WikiLeaks a lot in your novel. Has it achieved a mythic status — and if so, what does it represent?

TSR: Some of the fringe elements are definitely inspired by Wikileaks and Anonymous.

I think those elements arose as an antidote to what I felt was a one-sided vilification in the novel of the American right-wing — Blackwater, Haliburton and Cheney's cronies. I definitely lean more toward the left, and I think Wikileaks represents a very important impulse and the start of a strong movement toward anti-corporate sentiment and the demand for government transparency. (As ineffectual as that movement may end up being — because it started so late in the process of corporate control being consolidated...)

But I've also been around leftists for more than twenty years. Some of them are douchebags. I find it far from unthinkable that some leftist depopulation advocates would want to depopulate the globe for environmental reasons, as is one of the possible conspiracies in The Panama Laugh. The paranormal stuff, for me, just makes all that fringe stuff interesting.

10Z: Your novel also seems very aware of the latest ways that information gets distributed. There's viral YouTube videos, conspiracy forums, text messages, and one mysteriously-abandoned laptop. It's the contemporary details that most fiction leaves out, which somehow makes The Panama Laugh feel more real when information about the zombie attacks start turning up at CNN.com.

I feel like you and I lived in the center of a new kind of cutting-edge crazy during the dotcom boom, and it's nice to see someone channeling that into cutting-edge fiction. (There's even hacktivists in your book!) So do you sense a "big picture" about what's happening as new technologies come online, both in the U.S. and around the world?

TSR: I find it very interesting that Africa and South Asia seem to be getting wireless web technologies before they get wired ones. I think that'll affect the computer security environment enormously in the next ten years. And I think there are many very strange social implications for those of us who live our lives mostly online — good and bad.

Mostly, good. But I also think the possibility for disinformation is huge, which is some of what this novel is about.

10Z: When it came out in September, you did something interesting on the web. You're posting news blurbs — complete with links to the actual articles — about events which only happened in your novel. I did a double-take when I saw these headlines:

"Terrorist Group" Seizes San Francisco Building

San Francisco Cryopreservation Foundation Found Liable

And on Facebook, your novel also has its own page. Even though it's just been released, it's already won awards from...er, wait a minute. These are from your zombie counter-universe again, aren't they?

"2011 Crazed Hippie Disinformation Award" from Virgil Amaro Memorial Association.

"2011 It's Not Our Fault Award" from Bellona Industries Military Consultation (Juried Award).

"2011 Involuntary Termination Award" from mysterious international "Depopulation Activist" hacker group DePop Art.

TSR: Hah! Definitely, that's all disinformation. The novel is about corporate disinformation — think of this as my own little attempt to get incorporated. They're all characters and institutions in the novel.

10Z: In light of all that, it's funny that there's a disclaimer at the end. "The novel is fiction. Also, zombies aren't real." But wasn't it cathartic to describe the ruin and desolation of your old stomping grounds in San Francisco? I mean, you left San Francisco, moved to Sacramento, and then wrote a book where the zombies attack...San Francisco!

TSR: Oh, it wasn't vengeful. I love San Francisco! I was asked to write a zombie apocalypse set there, so I did....though I did it in the most roundabout possible way. It was really interesting to map out a route across a zombie-infested city that I know so well, and to invent all sorts of tunnels and things...

And the social stuff is all meant to feel very much like it could've really happened. To me, that makes the apocalyptic elements more interesting.

10Z: In the Talmud it says every man, in his life, should write a book. I believe they must've meant "a book about zombies." Imagine describing your home town in ruins — the police force abandoned, the high school laid to waste, every enemy converted into shambling undead. And not just your enemies — the whole invisible power structure.

But seriously, none of your friends are in the novel? I'm not sure I could resist the temptation! That jerk from the apartment upstairs? Zombie...

TSR: There are definitely no real people in the book. Strangely, that's not even a temptation to me. Even where characters are based on figures from the news, they're hybrids of several different people, and the institutions are all mixed up.

But there are dozens of Easter eggs to other books I'm working on...all of which concern paranormal stuff, which wouldn't be "real" in the context of the Panama Laugh universe. The only place where a real person showed up, in altered form, in the mythology was in the podcast "St. John of the Throwdown," which was written for Violet Blue to read and as such was inspired by her experience of being a homeless teenager. I wouldn't say that character is Violet, but she's certainly related.

10Z: So what kind of coffee do you have to drink to write about a zombie apocalypse?

TSR: Well, Temple has about the best damned coffee you'll ever drink. It's consistently rated highly in national terms. Of all the things that have been hard for me moving from San Francisco to Sacramento, Temple coffee makes it much easier. Any snotty San Francisco people who want to talk shit about Sacramento can face down a steaming mug of Temple's Ethiopian or Brazil Boa Sorte.

Click here to read Thomas's zombie apocalypse

Other Interviews:

Neil Gaiman has Lost His Clothes

Steve Wozniak vs. Stephen Colbert — and Other Pranks Jimmy Wales will Destroy Google

Nicholas Gurewitch: What Happened to the Perry Bible Fellowship?

The D.C. Madam Speaks!

James Ketchum: Hallucinogenic Weapons — the Other Chemical Warfare D.C. Sex Diarist Bares All

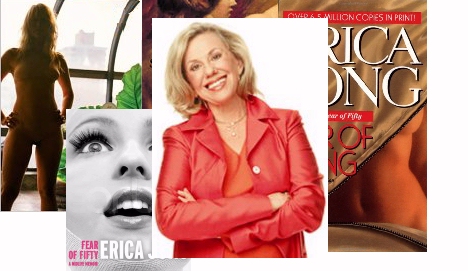

Beyond the 'Zipless Fuck' with Erica Jong

.jpg)

While no one would accuse Republican psycho and democracy killer Katherine Harris of being an advocate of sexual libertinism, some did suggest that she was using her best assets in a series of photos taken early in her campaign to become the Republican Senator from Florida.

While no one would accuse Republican psycho and democracy killer Katherine Harris of being an advocate of sexual libertinism, some did suggest that she was using her best assets in a series of photos taken early in her campaign to become the Republican Senator from Florida.

RU: Are you talking about Phil (Bronstein, Executive Editor of the SF Chronicle)?

RU: Are you talking about Phil (Bronstein, Executive Editor of the SF Chronicle)?

Neil Gaiman didn't arrive naked when he graced our MondoGlobo studio on Sunday, October 1. But according to a

Neil Gaiman didn't arrive naked when he graced our MondoGlobo studio on Sunday, October 1. But according to a